The Benefits of Merit Pay? New Study Shows That Federally Funded Teacher Bonuses Led to Improved Student ...

NewsfeedThe Big Picture

The Benefits of Merit Pay? New Study Shows That Federally Funded Teacher Bonuses Led to Improved Student Performance

Photo credit: Mathematica Policy Research

Photo credit: Mathematica Policy ResearchTALKING POINTS

- A new study indicates that teacher bonuses funded under the federal Teacher Incentive Fund modestly improved student performance in both reading and math

- Large pluralities of teachers severely underestimated the size of the bonuses available to them, or didn’t realize they were eligible to receive bonuses at all

New research conducted by Mathematica Policy Research attributes small improvements in student achievement to merit pay systems established under the federally funded Teacher Incentive Fund. While the overall effects of the program were generally positive, less than half of school districts surveyed said they intended to continue paying performance bonuses after federal grant dollars ran out in 2016, citing problems with program sustainability and awareness among educators.

Mathematica’s study is the latest of four commissioned by the Institute for Education Sciences to assess the effectiveness of federally funded merit pay. Established by Congress in 2006, the Teacher Incentive Fund has distributed $1.8 billion in four rounds of grants to districts across the United States that agreed to institute teacher and principal quality evaluations.

The findings offer a new data point in the long-running debate over the efficacy of merit pay. A handful of widely publicized studies have identified no academic returns from paying more money to teachers and administrators rated effective, leading one outspoken critic to dismiss performance bonuses as “the idea that never works and never dies.” Other experts have disagreed, pointing to the potential recruitment and retention benefits of identifying and rewarding top educators.

In the Mathematica series, researchers reported on the year-by-year implementation of merit-based teacher pay incentives in over 130 school districts from the 2010 cohort of grantees. Authors studied school surveys from all districts and student performance data from 10 specially chosen districts (131 schools total, with testing data drawn from students in grades 3-8) between the 2012-12 and 2015-16 school years.

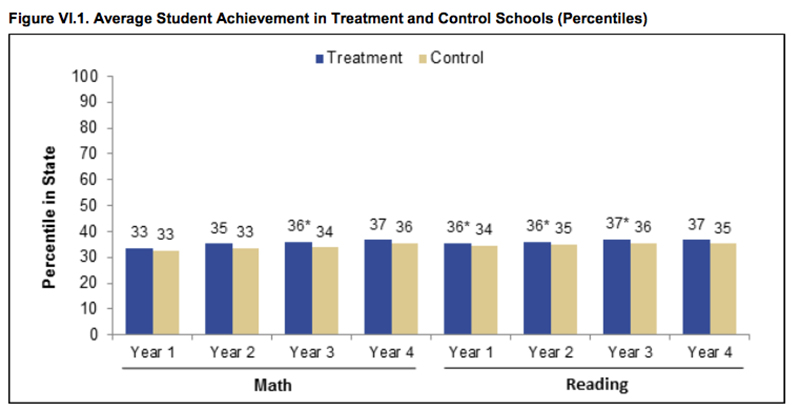

In both reading and math, students in evaluation districts made clear, if modest, gains over the four years of the TIF program. After the first two years, pupils’ performance in both subjects improved by 1-2 percentage points compared to statewide averages. That amounts to roughly 3-4 weeks of instruction across the four years of the program.

While the gains measured by Mathematica aren’t huge, the costs of the program — an average bonus of $2,000 for teachers, and $4,000 for principals — are lower than those associated with other interventions, the authors argue.

“A cost-effectiveness analysis suggests that pay-for-performance was more cost-effective than class-size reduction (through four years of program implementation) and about as cost-effective as providing transfer incentives for high-performing teachers to move to low- performing schools (at the end of two years),” they write.

Specifically, the per-pupil cost of the performance bonuses was $196 per student, compared to $193 per student in transfer incentives to achieve the same amount of testing growth.

Even as they recorded noticeable improvements, however, the majority of participating districts from the 2010 cohort also reported persistent frustrations. In each year of the program, more than half of all districts (63 percent in Year Two, 48 percent in Year Three, and 58 percent in Year Four) cited financial sustainability of TIF as a major concern. Unsurprisingly, just 47 percent of districts said they planned to continue awarding performance-based bonuses after their grant money expired.

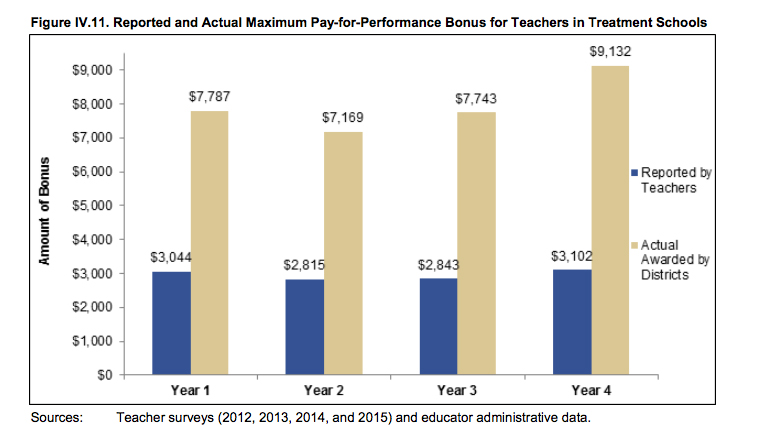

Another shortcoming: A large plurality of teachers in participating districts either didn’t realize they were eligible to receive bonuses for improved student achievement or significantly underestimated the size of the pay bump.

Just over 60 percent of instructors in participating districts understood that they could receive bonuses for improved performance after the first year of the program. Making matters worse, teachers believed that the maximum bonus they could receive was no more than 40 percent of its actual size. Although understanding of the details of the program was generally higher among principals, many were ill-informed of the potential rewards available to them.

Submit a Letter to the Editor

Tidak ada komentar